The mess that is ownership and licensing of WordPress contributions

Every day, thousands of people around the globe wake up, sit down at their desks, a coffee shop, or wherever they’re most comfortable, and open up the Making WordPress Slack instance, or a page on wordpress.org. And every day, those people contribute. WordPress—the software, the community, and the ecosystem—would not be where it is today without these dedicated people, some paid by employers or individual backers, some contributing in their free time.

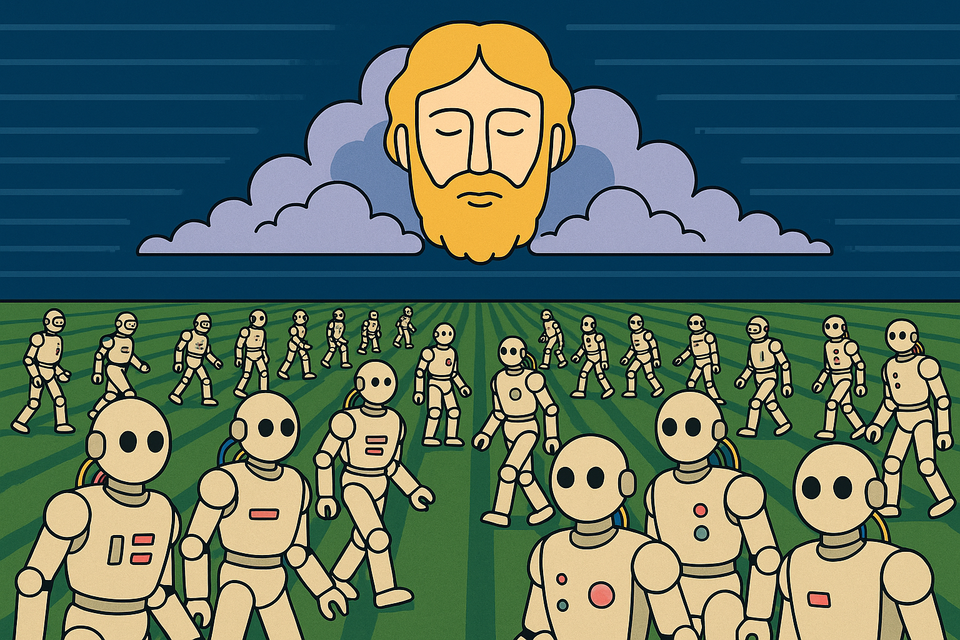

Pour one out for the contributors to WordPress.

Every contribution—whether code, documentation, translation, event planning, forum moderation, and more—is valuable to the overall ecosystem and to the community. And every contribution comes from a person, like you and me. When we choose to give our time to WordPress, we’re volunteering for project that’s spreading open source ideals and working to “democratize publishing.”

But in that gift lies a question: who or what are we volunteering for?

Answering this question is actually quite complicated because, as you’ll soon read, it depends on your contribution. While your contribution benefits the entire ecosystem, there is nuance to who or what entity you’re volunteering for, due to the structure of the people and organizations surrounding WordPress.

Let’s look at three distinct contribution cases.

1. WordPress & WordPress.org Code Contributions

“WordPress” started solely as software, created as a fork of B2 by Mike Little and Matt Mullenweg. Early contributions were from volunteers—including Little and Mullenweg—who were not paid for their work.

Fast forward to today and thousands of people have contributed code to WordPress, powering a significant portion of the web today. It’s fascinating to think that a single line of code contributed in 2010 might now be running on millions of websites on the internet. The impact is immense.

But who “owns” code contributions? Or, put another way, who “owns” the WordPress software?

While WordPress.org hosts the authoritative repository for the WordPress codebase, WordPress.org does not “own” any aspect of the WordPress codebase. Primarily, this is because WordPress.org is not an entity, nor a person, but there’s more to it than that.

The WordPress project has no “copyright assignment” policy or requirement. This means that every line of contributed code remains owned by the person who contributed it, regardless of how old the code is. Because code contributions are licensed under the GPL, they can be freely distributed inside of the WordPress codebase.

Some open source projects require contributors to give up the copyright on their code, assigning it to an entity who either solely or jointly (with the contributors) owns the code. OpenOffice.org maintained a controversial copyright assignment policy, which benefited its then-owner Sun / Oracle.[1] Such copyright assignment can be beneficial for open source projects—it may be advantageous to re-license code to a more favourable license in the future and ownership of the copyright allows projects to easily re-license. Mozilla famously re-licensed its entire codebase, which took five years. The effort required contacting every single contributor[2] and getting signed permission to relicense their code. Of course, look no further than Elasticsearch for how this can go completely wrong.[3]

Thankfully, with the WordPress codebase, relicensing is not something we need to worry about: no central entity, non-profit or otherwise, has ownership of the code. Instead, each individual contributor retains their rights.

So, let’s go back and answer our question for this scenario: who ”owns” code contributions? You, me, and every other code contributor. While our code is authoritatively hosted by WordPress.org, the code will always be yours.

2. WordPress.org Content Contributions

As has been well-covered as part of the WP Engine v Automattic case, WordPress.org itself is owned and operated solely by Matt Mullenweg. WordPress.org is also the hub of the community, holding all “official” WordPress content. Outside of code like plugins and themes,[4] WordPress.org content includes everything from end user and developer documentation to forum posts and translations.

Once contributed, who owns the content on WordPress.org? What license is it under?

When it comes to content contributions, there is no standard answer for what license your contributions fall under. Most sites that allow user-generated or user-contributed content include a terms of use, or other set of guidelines around content creation. For example, WordPress.com requires you to agree to a Terms of Service before creating an account or logging in. But, WordPress.org only requires that you read and agree to its privacy policy before creating an account.

Because there are so many kinds of content that exist on WordPress.org—and, as you’ll see, because they have varied licensing policies—it’s helpful to look at a few examples:

- Words you write on make.wordpress.org sites (e.g. posts, comments, handbook updates) have no disclaimer or notice regarding licensing.

- Except the make/docs site, which has a page about licensing that notes that contributions to the documentation team’s site (make.wordpress.org/docs) are licensed under the CC0, with the exception of code snippets that are under the GPL.

- The aforementioned make/docs page also notes that both end user and developer documentation are included by the CC0/GPL licensing split, which covers quite a bit of content.

- Except, while the make/docs page says it includes developer.wordpress.org, ”Notes” contributed to the developer.wordpress.org code reference state they are licensed under the GFDL (for example, when logged in).

- The WordPress.org Photo Directory explicitly states that submissions are licensed under CC0.

- “Learn WordPress” courses are licensed under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

- Creating a new post in the support forums, or responding to a post, includes no licensing information.

- Similarly, no licensing information is available when creating new patterns.[5]

- A large number of contributors translate strings into dozens of languages, which appear in both WordPress and across WordPress.org and related web properties. WordPress.org’s GlotPress installation, which is used by the community to translate WordPress, allows anyone, globally, to login and start contributing translations. Nowhere is it clear how translations are licensed.

While there are other contribution areas, the above encompasses some key scenarios. What we can pull from these scenarios is three-fold:

- Some content is clearly licensed under a mixture of the GPL, GFDL, CC0, and CC BY-SA 4.0 licenses.

- Some content has no license, no indication how it can be used.

- In the case of licensed content, there is occasionally (but rarely) a notice to either end users or contributors regarding licensing.

This is a problem.

Combining 1 and 3 above gives us a few conclusions. First, under the GPL, content should list clear ownership, and when those owners are “Contributors”, it should be possible to generate a list of all such contributors (e.g. using version control). But more problematic is that content under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license explicitly requires attributing credit to the creator(s) of the work, which nominally owns the copyright their creation. That is not WordPress.org, which we now know is not an entity. It’s also not Mullenweg. But content licensed under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license doesn’t actually list the creators of the work.

The combination of 2 and 3 above highlights, perhaps, the greater problem. Forums across the internet[6] detail terms of service, which must be agreed to before posting content. While such terms are incredibly verbose[7] and full of legalese, those terms define what rights content creators have and what rights they may be signing away to the site owners. Because WordPress.org has no such terms and defines no such rights, in areas where no license is defined pre-submission, what ownership and licensing rights exist? To understand how each piece of content is licensed, do we need to contact each individual owner?

Legally, creators retain full ownership of their individual works. The strings I translated on translate.wordpress.org are mine—I own them and they cannot be sold or republished without my permission. Without an explicit license defined pre-contribution, technically, I can decide my strings are under whichever license I would like. Perhaps the strings I translated are fully under my copyright and cannot be used within WordPress without my explicit consent.[8]

Now, multiply this scenario by the millions of contributions across tens of thousands of contributors over the past twenty years. It’s accurate to say that some people understand their contributions are GPL or CC licensed. But, do most? And what about content with no licensing information?

3. WordCamp Organizing & Speaking

The final contribution area that’s worth covering is perhaps the most complex. Before the start of the COVID pandemic in 2020, there were well over 100 WordCamps per year and many more meetups, on all six habitable continents. The growth of WordCamps facilitated the growth of the WordPress community and helped bolster the overall ecosystem. It goes without saying that WordPress would not be “WordPress” today without WordCamps and meetups.

A couple of weeks ago, an interesting thread appeared on Twitter, causing a small WordCamp US controversy sparked by a misstatement. This was corrected in the thread, but I’d like to hone in on one response to the thread, from Sé Reed:

Karla, please excuse my erroneous assumptions re your employment (and humanity), and be informed that you cannot legally volunteer for a for-profit company: https://webapps.dol.gov/elaws/whd/flsa/docs/volunteers.asp

Previously, I detailed the activities that run through the WordPress Foundation, noting that WordCamps and meetups explicitly do not run through the WordPress Foundation. Instead, in 2015, those events were spun out into the for-profit WordPress Community Support (WPCS) “public benefit corporation” that is wholly owned by the WordPress Foundation.

Reed’s tweet notes that Americans cannot legally volunteer for a for-profit company.[9] WPCS is a for-profit company. When you help organize a WordCamp like WordCamp US, when you speak at a WordCamp, when you “volunteer” at a WordCamp, your time and effort are being donated to a for-profit company. You are, for all intents and purposes, a volunteer of that company. IANAL, but by my read, this is illegal.

According to the “Fair Labor Standards Act”, individuals may not volunteer at for-profit companies, even if they want to. Had WordCamps and meetups remained under the remit of the WordPress Foundation, this would not be a problem at all, as individuals are absolutely allowed to volunteer for non-profits. Once WordCamps moved to a for-profit entity, “volunteering” fell afoul of US labor law.

Now, it’s unlikely this situation is going to get ”flagged” by the US Department of Labor. It’s also unlikely to be litigated. However, it makes you wonder: why are WordCamps under a for-profit? Who is that benefiting? This situation would not exist had WordPress events remained a part of the WordPress Foundation. Is there a ”workable” state where events could have remained under the WordPress Foundation?

It’s notable that “legal structure for community events” is a solved problem within the open source ecosystem. Consider the numerous open source communities that hold community-organized events. This is a common theme: the open source ecosystem has faced many, if not all, of the same challenges the WordPress community faces but, due to a strong “not invented here” syndrome, our community has not benefited from this collective knowledge.[10]

What about WordPress.org content contributions again?

With this additional context, it’s important to circle back to WordPress.org content contributions as a key scenario. Those contributions end up a part of WordPress.org, stored in its database. While that site has no terms of service, we know it’s owned personally by Mullenweg… don’t we?

To me, it has always seemed unlikely that Mullenweg operates WordPress.org as an individual. More likely is a scenario similar to Mullenweg’s hosting of sites belonging to Eric Meyer, Kelly Dean, and Joe Clark, among others. Those domains use mobiusltd.com nameservers, and a quick check reveals a lot of other domains that have used mobiusltd.com nameservers,[11] the most notable of which is, perhaps, wordpressfoundation.org.[12]

Visiting “mobiusltd.com” shows that it is yet another company owned and operated by Mullenweg.

Now, WordPress.org does not use mobiusltd.com nameservers, though WordPress.net, which hosts community subsites, does use mobiusltd.com nameservers. Thus, there’s no easy way to determine what person or organization “owns” or “operates” WordPress.org, but it seems reasonable to assume it is owned by “Mobius Ltd”, a for-profit company Mullenweg spun up to oversee his personal infrastructure.

If WordPress.org is owned by Mobius Ltd, are contributions to WordPress.org “donations” to that for-profit company?

In allowing WordPress.org to remain his personal property, or part of his personal company, and not part of a non-profit organization like the WordPress Foundation, Mullenweg has created a very unusual situation, whereby individuals ”volunteer” for entities that seemingly cannot accept contributions, and do so without an understanding of how their contributions will be used across the web.

Frankly, this is a mess. If it ever becomes important to unravel the licensing, ownership, and labor issues, the process could take years.

The community ultimately forked the project and established what is now the de facto open source Microsoft Office competitor. LibreOffice is backed by a neutral foundation, with transparent governance. The pace of development increased after forking, not only because of an increase in contributions but also because milestones were no longer tied to a single corporate interest. Oracle eventually discontinued OpenOffice, donating it to the Apache Software Foundation, where it still withers today. ↩︎

Or ”estate” in the case of a deceased contributor. ↩︎

Elastic, the company behind Elasticsearch, relicensed Elasticsearch under the SSPL, which is not an OSI-approved license, and which is not considered truly “open.” Amazon ultimately forked Elasticsearch, creating “OpenSearch.” Meanwhile, Linux distributions dropped Elasticsearch. ↩︎

Like the WordPress codebase, WordPress plugins and themes are exclusively owned by their contributors and licensed under the GPL. Unlike the WordPress codebase, the vast majority of plugins and themes are not authoritatively hosted on WordPress.org. ↩︎

Now, theoretically, all code on the site is, in some way, derivative of WordPress, making it de facto licensed under the GPL, but when someone logs into WordPress.org and immediately starts contributing, this is never made clear. ↩︎

For example: Facebook, Reddit, Bluesky, Something Awful. ↩︎

Unlike this writer. ↩︎

”All rights reserved.” ↩︎

The laws may be applicable in other jurisdictions. IANAL. ↩︎

In the past, specific individuals have worked to bridge the gap between the WordPress community and the rest of the open source community, but Mullenweg has been less inclined, so that effort has stagnated. ↩︎

Some of the domains are flashbacks to Web 1.0. Others appear to be early ideas that never came to fruition. The fun domains, like “traumattic.com”, appear to be proactive squatting. ↩︎

Tangential to this post, but this implies that the WordPress Foundation’s website is hosted by Mullenweg. Is this an in-kind donation from Mullenweg to the non-profit? If so, where is this in-kind donation noted or otherwise tracked? If not, is the WordPress Foundation compensating Mullenweg for this hosting and where is that disclosed? ↩︎

Member discussion